Basics of Groups and Group Representations

The natural world around us is rife with examples of transformations applied to objects that retain some underlying property of the object before and after the transformation. For example, rigid motions in 3D-space that preserve a particular molecule. A simple example is rotation of a 2D square ( in \(XY\) plane ) about the \(Z\) axis. A 0, 90, 180 and 270 degree rotation has no impact on the square shape and orientation. Such transformations are called symmetries.Two symmetries can be combined to form another symmetry and every symmetry has an opposite or inverse symmetry. For instance, 90 and 180 degree rotation can be combined to produce a 270 degree rotation that does not change a square. Also,a rotation counterclockwise by 90 degrees can be undone by rotation clockwise by 90 degrees. Groups are a collection of transformations that preserve some underlying structure of a set to which they are applied.

Historically, groups were not separate from their representation as a set of transformations. However, in the late nineteenth century Cayley formulated an abstract definition of a group that separated it from it from its representation as a group of transformations or tranformation groups . This enabled effective study of transformations which might drastically differ in how they are represented but in essence can be defined as the same generic abstract objects. Representation theory aims to understand different ways in which groups can be realized as linear transformations of a euclidean space.

1. How is group theory relevant in machine learning

In machine leanring there are several tasks that require classification, prediction and detection of structured data. For classification it is requried that that the output of the model does not change with change in orientation or position of the strcutured data ( invariance ). For prediction and detection tasks, it is required that the output of the model changes in the same way as the change in input (equivariance). For instance, a model that detect the co-ordinates of a person in a pitcure on the left, should be able to detect the correct co-ordinates of the same person if the location of the person changes.

Traditionally, the way to achieve invariance in the output of the machine leaning model is data augmentmentation. This however has several disadvantages:

- This does not guarantee invariance as it is not possible to take into account every possible chaange in input data structure that should not impact thje model output via data augmentation.

- Data augmentation can significantly increase training time and resources.

- There is significant redundancy in features learned by the model.

What if the machine learning model learns features of the input data taking into account the underlying symmetries in the data? For example, CNNs have translational invariance and equivariance built in its model opeartions. In CNNs, convolution operation ensures translational equivariance and pooling operation ensures translational invariance.

This is where group theory can help. If we know the underlying symmetries in the data, we can ensure that while designing the model, we use those operations ( tranformations) that preserve those underlying symmetries. This would ensure that we no longer need additional processes like data augmentation to achieve a more reliable model that is efficient to train. Models that take care of handling underlying symmetries allow for greater weight sharing and learn more efficient feature representations by utilizing symmetries in the input data.

2 Abstract Groups

A Group is a set \(G\) which is closed under an operation \(∗\) (i.e., for any \(x, y \in G, x ∗ y \in G\)) and satisfies the following properties:

- Identity: There is an element \(e\) in G, such that for every \(x \in G, e ∗ x = x ∗ e = x\).

- Inverse: For every \(x\) in G there is an element \(y \in G\) such that \(x ∗ y = y ∗ x = e\) , where \(e\) is the identity.

- Associativity: he following identity holds for every \(x, y, z \in G:x ∗ (y ∗ z) = (x ∗ y) ∗ z\).

A group that is also commutative i.e. for every \(x, y \in G: x ∗ y = y ∗ z\) is called an abelian group.

A Subgroup is a subset of a group that also a group in its own right.

A Field is a set \(F\) which is closed under two operations \(+\) and \(*\) such that:

- \(F\) is an abelian group under \(+\) and

- \(F\) − {0} (the set \(F\) without the additive identity 0) is an abelian group under \(*\).

2.1 Examples of Abstract groups

2.1.1 General Linear Groups and Special Linear Groups

General Linear Group \(GL_n(F)\), is a non-abelian group of inveritible \(n \times n\) matrices under the operation \(*\) where \(*\) represents matrix multiplcation. Since the matrices in this group are invertible, the determinant of the matrices in the group is non-zero. The entries of the matrices can come from real the field of real numbers \(R\), rational numbers \(Q\), complex numbers \(C\) and quotitent group \(Z_p\)

Special Linear Group \(SL_n(F)\) is a subgroup of \(GL_n(F)\) with the determinant of the matrices being one.

2.2 Group Homomorphism and Isomorphism

Homomorphism is a mathematical tool to compare two groups. it is used to identify whether two groups are similar, identical or completely dissimilar. Let us start with an example:

2.2.1 Example

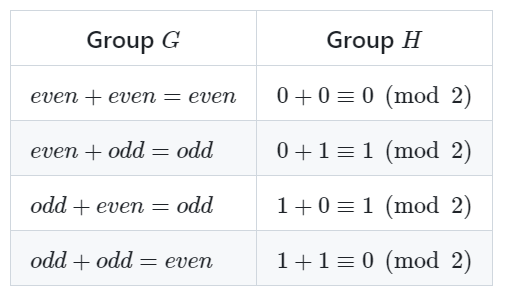

Consider two groups:

- \(G(Z, +)\): Infinite group of all integers

- \(H(Z/2Z, +)\): Finite group of integers mod \(2:\{0, 1\}\)

At the surface, these two groups seem to be complely different with no similarities. However, closer examination of group \(G\) reveals that:

\[G = \{ odd \} \cup \{ even \}\]if we consider \(G\) as a group with two kind of elements, \(even\) and \(odd\), and compare it with \(H\):

we can see that its behavior of the two groups is very similar. More formally, Let us consider a function \(f\) that maps each even element of G to \(0 \in H\) and each odd element of G to \(1 \in H\):

\[f: Z \rightarrow Z/2Z\]If we apply \(f\) to every element of G, we can see that G and H are actually very similar.

2.2.2 Generalization

In general, a function that given two groups \((G,*)\) and \((H, \circ )\) maps every element of G to an element in H i.e.

\[f: G \rightarrow H\]such that, \(f(x*y) = f(x) \circ f(y)\), where \(x,y \in G\) is called group homomorphism or homomorphism in short.

if such a function exists, this implies that the two group have some underlying structural similarity. Note, that the function \(f\) is not required to be bijective and the direction of mapping from one group to another matters.

if \(f\) is bijective then the groups are not just similar but identical. Such a function is called group isomorphism or isomorphism, in short.

3. Transformation Groups

To understand what a transformation group is, we need to clearly define transformation. A transformation of a set X is a bijective self-map \(f : X \rightarrow X\). i.e it is a function that when applied on a set returns the same set. A transformation is also called a permutation of a set \(X\).

Two transformations can be composed to produce a third, and every transformation has an inverse transformation (this is essentially the meaning of bijection). In other words, the collection of all transformations of \(X\) forms a group under composition, whose identity element is the identity transformation \(e\) fi xing every element. Such a group is called Aut X or Automorphism of set \(X\)

A transformation group is any subgroup of Aut \(X\) for some set \(X\).

It should be understood that every abstract groups is isomorphic to a transformation group.

3.1 Examples of Transformation Groups

3.1.1. Dihedral group

A collection of symmetries of a regular n-gon (for any n > 3) forms the dihedral group \(D_n\) under composition. It is easy to check that this group has exactly 2n elements: n rotations and n reflections. \(D_n\) is non-abelian.

For example, \(D_4\), a group of all possible transformations of a square that ensures the same orientation and structure before and after the tranformations includes 8 elements: rotation by 0, 90, 180 and 270 dgrees, a horizontal flip ( or reflection ) and a vertical flip applied to each of the first four rotation transformations.

\(D_4\) is isomorphic to \(Z/8Z\). In general a dihedral group \(D_n\) has 2n elements and is isomorphic to \(Z/2nZ\)

3.1.2. Groups of Linear tranformation

A vector \(V \in R^n\) can be written as a column vector with \(n\)-elements. A linear transformation:

\[T: R^n \rightarrow R^n\]is a linear map which defines where it sends the basis of V. The group of such linear maps that preserves the vector space of a vector for a given basis is called the group of linear transformation as is defined as \(GL(R^n)\).This transformation is achieved by left multiplying an n x n matrix with the vector V. This implies that \(GL_n(R)\) is isomorphic to \(GL(R^n)\) for a given choice of basis.

This is true for complex numbers as well.

3.1.3.Symmetric Groups

A symmetric group \(S_n\) is the group of permutations of a set with \(n\) elements. No matter how one permutes the elements of a set, the set still remains the same. Hence, a symmetric group \(S_n\) is a finite transformation group with n! elements. There are many notations for describing a permutation, but the most convinient and compact is the cycle notation. A transposition(swapping) of elements of a set is represented as a tuple (s,d), where s is the element’s source index and d is the destination index. A cycle is represented as a tuple of more than two elements.

For example, Let \(S_4= \{1,2,3,4\}\)

-

Swapping the first two elements of the set is denoted as (1,2) which transforms \(S_4\) to \(\{2,1,3,4\}\).

-

Next is we wish to move the resultant set such that element at indexes move as follows: \(1 \rightarrow 2, 2 \rightarrow 3 , 3 \rightarrow 4, 4 \rightarrow 1\), the transform is denoted as \((1,2,3,4)\) which transforms the set resulting from transform in step 1 to \(\{4,2,1,3\}\).

-

Permutations can also be disjoint, for example \((1,2)(3,4)\) transforms the resultant set from step 2 to \(\{2,4,1,3\}\). The notation \((1,2)(3,4)\), denotes that first transposition \((1,2)\) is performed and then \((3,4)\).

-

Two permutations and be combined under the composition operator \(*\) to create a new permulation. The permutation are composed right to left. For example, Let \(S_4 = {1,2,3,4} , f = (1,2) , g=(2,3)\). Then f * g applied to \(S_4\) results in { 3,1,2,4}

The identity element of \(S_n\), is a fixed ordering of its element. Except for \(S_1\) and \(S_2\), all symmetric groups are non-abelien. Disjoint permutation however commute.

4. Continuous Transformation or Lie Groups

A lie or continous transformation group moves a point through a smooth manifold (curve). An example of lie group with one-dimensional manifold is a group of unit complex numbers: \(S^1\).

Let \(z \in S^1\) such that \(z = cos(\theta) + sin (\theta)\) and \(x \in C\) then:

\(y=z.x\) rotates \(x\) by \(\theta\) along a continous circle with every change in the value of \(\theta\).

Since, manifold of a lie group is smooth, it can be differentiated, integrated conviniently.

5. Group Actions

An action of \(G\) on any set \(X\) is a way to assign to each g in G some transformation of \(X\), compatibly with the group structure of G. Formally, A (left) action of a group \((G,*)\) on a set \(X\) ( finite or infinite), is a map:

\(G \times X \rightarrow Y\)

such that, \((g,x) \rightarrow g.x\) where \(g \in G, x \in X\) and it satisfies:

-

\(g_1 . (g_2 . x) = (g_1 * g_2).x\) , for \(g_1, g_2 \in G, x \in X\)

-

\(e_g.x = x\) for all \(x \in X\) where \(e_g\) is the identity of the group

Based on the first condition it can be said that group action is a group homomorphism.

Let us understand using an example:

Let \(X=\{1,2,3,4\}\) which includes the labels of vertices of a square labeled 1 to 4 starting with top right. When \(D_4\) acts on \(X\), transformation \(r_1\) ( rotation by 90 degrees), results in \(X\) being \(\{4,1,2,3\}\); a horizontal flip on X results in X being permuted by \((12)(34)\). The group action \(A\) on \(D_4\) can be written as:

\[A: D_4 \rightarrow S_4\]In the coming subsections we discuss orbits and stablizers. These are constructs that relate the structure of the group with the structure of the set they act upon.

5.1. Orbits

Two points \(x,y \in X\) acted on by a group \(G\) are called G-equivalent if there is an element \(g \in G\) such that when \(g\) acts on \(x\), it results in moving \(x\) to \(y\), i.e. \(y = gx\). Note that G-equivalent is an equivalence relation. This results in the set \(X\) being divided into equivalent classes where one class is all the points \(y\), that can be reached by \(x\) if every possible element of G acts on it. Each such class is called an Orbit. We can formally denote orbit of \(x\) as:

\[O_x = G.x\]5.2. Stablizers

All the elements of \(G\) which do not move an element \(x \in X\) when they act on it are called stablizers of \(x\). Formally, stablizer of an element \(x \in X, G_x\) is a subgroup of a group \(G\), such that:

\[G_x=\{ g:g.x=x \}\]6. Group Representations

The goal of representation theory is to understand the different ways in which groups can be realized as transformation groups, primarily, as groups of linear transformations of euclidean space. More specifically, it is group homomorphism from an group G to the groups \(GL(V)\) i.e.

\[G \rightarrow GL(V)\]The dimension of the representation is the dimension of the vector V. Every group admits a trivial representation on every vector space which sends very element of G to the identity transformation i.e. do not cause any change to V.

Following subsections give examples of group representations

6.1 Permutation Representation

Permuatation representation,\(r\) is a group homomorphism of \(S_n\) to \(R^n\) i.e.

\[r: S_n \rightarrow GL(R^n)\]For example for \(S_3, (12)\) can be represented as:

\[r=\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\]6.2 Left Regular Representation

Left regular representation,r, is a kind of permutation representation that is achieved by action of a group \((G,*)\) on itself. i.e. \(g * g_i\) where \(i=1,2...,\|G\|\) is a permutation of elements of the group in G. This is self-evident as a group is closed under its operator. This representation can be formulated as:

\[r: G \rightarrow GL(F^{\|G\|})\]A left regular represention \(L_g\) transforms a function \(f\) by transforming its domain via an inverse group action : \(L_gf(x) = f(g^{-1} x)\) where \(g \in G\)

Note: Refer [7] to undertsand why \(g^-1\) is used instead of \(g\)

6.3 Alternating Representation of \(S_n\)

Any transformation in \(S_n\) can be formulated as a sequence of transpositions between two elements of a set. If the number of such transpositions is even, the transformation can be represented +1 and if the number of transpositions is odd, the tranformation can be written as -1. More formally,

\[r: S_n \rightarrow \{\pm 1 \}= GL(F)\]Note, that this representation has a dimension 1.

6.4 Representation of \(Z_n\)

\(Z_n\) can be represented in 2 dimensions and visualized as two perpendicular axis rotating about the origin. After \(n\) equal rotations the axis comes back to its original position.

The representation is therefore a homomorphism such that:

\(r: S_n \rightarrow R^2\)

where, \(m=\{1,2,3,...,n\}\)